This article in the Boston Phoenix was published in mid october, 2000. Although predominantly about Freedonia, the author conducted a lengthy interview with Eric Lis, quoting him and speaking favorably about the Empire in general.

States of mind

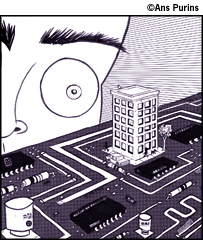

More than 100 make-believe 'micronations' exist on the Net. Now some are looking for actual homelands. Have they seceded from reality?

by Andrew Weiner

Summer is over, and John Alexander Kyle is headed back to college to begin his senior year. For the most part, his concerns aren't that different from those of his classmates at Babson: moving in, getting into classes, finding a job after graduation. But as the constitutional monarch of the Principality of Freedonia, Kyle, who prefers to be called Prince John I, also must tend to the affairs of a "micronation" of nearly 300 citizens.

Summer is over, and John Alexander Kyle is headed back to college to begin his senior year. For the most part, his concerns aren't that different from those of his classmates at Babson: moving in, getting into classes, finding a job after graduation. But as the constitutional monarch of the Principality of Freedonia, Kyle, who prefers to be called Prince John I, also must tend to the affairs of a "micronation" of nearly 300 citizens. Call it a minor in statecraft. In his spare time, Prince John consults his cabinet and works out amendments to the Freedonian constitution. He also drafts treatises on topics like gun control and taxation. His biggest task, though, is to put Freedonia on the map. Literally.

That's because Freedonia doesn't exist, at least not in the way that countries like Turkey and Mexico exist. It doesn't even exist in the way that Monaco or Vatican City exist. If a nation without territory is a strange concept to grasp, that's because Freedonia is precisely, and only, that: a strange concept.

Most nations start with land and worry about principles later. But having laid claim to a corner of cyberspace, Freedonia -- like a handful of other micronations -- has begun to assert its sovereignty in other, less virtual realities. To hear Prince John tell it, nothing less than the destiny of humankind is at stake in the attempt.

States of mind

(continued)

by Andrew Weiner

The first Freedonian republic was actually an oligarchy, with all authority vested in two presidents and several cabinet members. Although the risk of revolution was rather low -- Freedonia had no citizens who were not also rulers -- John gradually moved to consolidate his power. Four years later, the second president was removed; a year after that, the country was re-established as a constitutional monarchy under the new Prince John I.

Why a monarchy? John gives two reasons. The first is that a life term renders him immune to the pressure of special interests, which he holds responsible for the downfall of representative democracies. Second, and perhaps more important: he's the right prince for the job.

Most college students don't tend to say things like "Whether or not we see a nation of liberty on this planet could hinge largely on my competence." Then again, most college students aren't self-proclaimed royalty. I didn't have the chance to meet John in person (he chose instead to communicate by e- mail), but our correspondence left me with the impression of someone exceptionally serious, if somewhat shy. He doesn't use slang or even contractions, and he signs his correspondence "Yours in Liberty." His chief hobby is improving his qualifications for princehood by studying political philosophy and keeping up with international news.

John's attention to theory is reflected in the Freedonian constitution, a lengthy document larded with such baroque legalisms as "bills of attainder" and "letters of marque and reprisal." Its frequent overlaps with the US Constitution reflect a little cribbing, perhaps, but also the desire of Freedonia's founders to return to essential principles that, in their view, have been largely neglected by American leaders.

Chief among these is a thoroughgoing, nearly utopian libertarianism. Should Freedonia ever become an actual state, its citizens will enjoy a condition of virtually limitless freedom. All drugs will be legal. There will be no speed limit. Gun ownership will be unrestricted and taxes will be "ultra-low." Underscoring these views is a simple faith that, if left to their own devices, people will find a way to get along. Since a prosperous private sector is sure to result, the Freedonian government plans to offer no social services and to spurn public-works projects entirely.

But if John and his fellow Freedonians trust optimistically in the benevolence of human nature, they are hostile toward any and all acts of government intervention. (Perhaps this reflects the peculiar position of a nation whose founders were being unjustly repressed by 10 o'clock curfews.) The problem with virtually every society, they believe, is that individual freedom is subject to "preventative" laws restricting behavior that hasn't yet occurred. Prince John derides this overreaching as "the punishment of the whole for the acts of a few."

Prince John's message has found a number of takers -- 275 at last count. Freedonians, according to their ruler, are "a widely varied people." This is almost true. Freedonians range in age from 12 to 72, and hail from nations as varied as Croatia, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia. They work as programmers, plumbers, poets, and parapsychologists. But it is worth noting that only six Freedonians are women.

Because the country has not yet formed an active parliament, the responsibility for governing lies exclusively with Prince John and his cabinet. But even for the nation's ruling class, power exists more as concept than as fact. Dustin Gawrylow tells me that when Prince John asked him to be Freedonia's prime minister, "I had only one question: `Can I declare war?' [John's] answer was, `Well, theoretically, yes.' " For the majority of Freedonian citizens, however, there isn't a whole lot more to do than just belong.

Freedonia is not the only micronation to have declared its sovereignty in the past five years. The most comprehensive Web listing of micronations contains 118 entries; only a handful predate 1995. This recent surge in do-it-yourself statecraft is entirely due to the establishment of the Internet, a vast and uncharted terra incognita with boundless tolerance for far-fetched ideas.

Unsurprisingly, then, a wide range of interests and tastes is represented in micronational political culture. Many exhibit a weakness for the kinds of names found in Dungeon & Dragons modules or bad fantasy novels: the Dominion of Asphynxia, the Barony of Telusia, or the Glorious Empire of Lafartia. Royal-sounding titles are a common fetish, even in republics; roman numerals are also popular. Sometimes, various kinds of celebrity are conflated, as in the case of His Grace, Grand Duke James Dean and His Excellency, Archbaron John Wayne, both of the Republic of Tulsa.

Micronations also exhibit a deliriously random range of motives and symbolic references. Take, for instance, the Inner Realm of Patria, a "de facto Hindu theocracy" that boasts the same flag as an international shipping concern and a motto borrowed from a Stephen Stills lyric. Similarly scattershot is the 1st Independent Stoner Homeland, an affiliate of the pro-pot Green Panther Party, whose mock constitution makes high-minded appeals to turn Northern California into a state called Ganjastan and, in the next breath, defends each Ganjastani's inalienable right to "Party!"

For many of these virtual Grand Viziers and Supreme Dictators-for-Life, becoming masters of their own domains has been a lifelong hobby. More than a few admit to having dubbed themselves kings of their own bedrooms as children. Eric Lis, Emperor of Aerica, explains: "All children make up imaginary lands and stories, imaginary friends and adventures. I just never grew out of mine, and a couple hundred people have gotten pulled in along the way."

Aerica, which calls itself the "Monty Python of Micronations," displays a fairly typical national character: earnest calls for peace, equality, and freedom are leavened by a gently self-deprecating sense of humor. When Eric describes his nation's values to me, he stresses the need for both "iconoclasm and diplomacy," for speaking one's mind and respecting the views of others.

It's this balance that seems to be missing in the more uncompromisingly serious micronations like Freedonia. Lost amid the flourishes of para-libertarian rhetoric is the fact that ample freedom of speech already exists both in cyberspace and in many of the countries that unknowingly host these would-be splinter states. After all, the First Amendment guarantees every American the right to proclaim herself Exalted Arch-Solipsist of Dementia, should she so choose.

In fact, the Freedonians and the Ganjastanis probably owe less to the Founding Fathers than they do to the members of a different tradition in American politics: the local crank who proclaims himself king. The most famous of these, San Francisco's legendary Emperor Joshua Norton, printed his own bonds, issued executive orders, and gained such notoriety that his funeral in 1880 boasted 10,000 mourners in a two-mile parade.

States of mind

(continued)

by Andrew Weiner

Today Talossa has annual political congresses, several newspapers, and a fully functional invented language, akin to Esperanto. Moreover, Talossans have augmented their two decades of actual history with a mythical genealogy. A 1994 law decreed, for example, that all Talossans are "inexplicably and inextricably connected somehow to Berbers."

Although Talossans are aware that they operate from a position of what they call "impaired sovereignty," they have succeeded in creating for themselves an actual homeland, of sorts, on some five square miles in the East Side of Milwaukee. A Talossan can go to the neighborhood laundromat and simultaneously be in the Buffonia canton of the Maricopa province.

But only a small handful of leaders try to shepherd their people from the collective fantasy of chat rooms into reality. In the annals of micronational history, only once has a micronation actually been successful in claiming a homeland.

The man behind this stunt was Roy Bates, a British veteran who used squatter's rights to claim Roughs Tower, a defunct anti-aircraft battery built on a platform in the North Sea, six miles from the British coast. Bates quickly redubbed himself Prince Roy and his new home, Sealand; his wife and son soon joined him. This was in 1967. Although the British government has tried on occasion to evict the self-proclaimed royal family, a combination of favorable legal rulings and bureaucratic indifference has enabled Sealand to remain more or less sovereign.

The prospect of a tax-free, lawless fiefdom within miles of European borders has prompted various sorts of shady dealing. Sealandian passports have reportedly turned up in the hands of European drug traffickers, and, strangely enough, on the corpse of Andrew Cunanan, the murderer of Gianni Versace. Although Prince Roy does issue official papers to citizens of Sealand, he has vehemently denounced these passports as forgeries.

But Roy has involved Sealand in other schemes, the latest being a start-up called HavenCo. Founded by a young MIT dropout named Ryan Lackey, HavenCo styles itself the Internet equivalent of a Cayman Islands bank account: a "data haven" free of any and all government regulation. Cyber-gambling, pyramid schemes, and extra-kinky content will all be permitted, though HavenCo will refuse to sanction spamming, money laundering, or kiddie porn. The project is still some ways from completion, but Lackey has already secured $1 million in venture capital.

Freedonia's Prince John, however, dismisses Sealand as a "squandered" opportunity to create a more idealistic libertarian state. For the past several years, John himself has spearheaded an effort to convert the political dreams of his countrymen into actual territory. Freedonians first investigated the possibility of a "freedom ship" that would sail in international waters. The construction of an artificial island was also discussed, but both options were rejected in favor of a scheme to secure land.

Because it lacks a standing army, Freedonia had to rule out secession or annexation. So Prince John and his cabinet have been looking into real estate. Their most promising opportunity is in Somaliland, an East African breakaway nation that declared its own independence in 1991 but has yet to be recognized by the international community. According to John, the sultan of a Somaliland province has indicated his willingness to cede a block of land to the Freedonians in exchange for work on several economic-development projects.

The settlers would be responsible for building an asphalt highway through the province and for constructing a seaport. Freedonia's lack of restrictions would, John predicts, make the port attractive to shipping lines and commercial fisheries. The country's low taxes would also make it an attractive residence for the wealthy -- a cross between Monte Carlo and Liberia.

Right now, the biggest thing standing between Freedonians and Freedonia is money. Prince John estimates that the necessary construction would cost something on the order of $1 million. To this end, the country has begun minting currency in the form of silver coins. But the nation's coffers presently lack even the funds to send John and his advisers to Somaliland for a fact-finding mission. Without a surprise benefactor, Freedonia appears unlikely to take physical form anytime soon.

But according to Daniel Partan, a law professor at Boston University, the scheme is at least plausible in theory. No statute of international law explicitly prohibits an existing state from ceding territory to a start-up micronation. It's just that a huge gulf -- or maybe just a lack of firepower -- stands between calling yourself a country and being recognized as such by the international community.

It's ironic that the same benevolent idealism that made Freedonia a successful micronation prevents it from commanding any respect in reality. Or maybe it's only fitting. Then again, though, political history has time and again been altered by social experiments that once seemed like strange ideas. So if current fantasy states give way to an archipelago of private Idahos, you will owe your thanks to Prince John I -- and maybe your fealty, too.

Back to the Aerica main page Back to the Museum!